1980 Wolverine Football Team Rode Mid-season Change into Unprecedented Championship Run

Moments That Changed Wolverine History: Part Two of a 12-part Series Looking Back at Events Which Changed the Landscape of Woodruff Athletics

By: Garrett Mitchell, Staff Writer

The number on the back of Tron Jackson’s jersey grew smaller as the gap between he and the Woodruff defenders trying in vain to run him down grew ever larger.

Jackson, Liberty High School’s star and future University of Georgia running back, carried not only the football with him, but also the Wolverines’ potential hopes of playing for a sixth consecutive 2A state championship.

“Liberty had Tron Jackson, and I was put back there to stop him if he got through the line,” recalled Woodruff quarterback Darrell Johnson, who also played some at defensive back. “He got through and I couldn’t catch him in 80 yards.”

Jackson’s run proved to be the dagger. The Red Devils toppled the heavily favored Wolverines 19-13 on that crisp, early October night in 1980. It was Woodruff’s second loss of the season in seven games, though it was by far the most crushing.

Liberty and Woodruff resided within the same region, and in 1980 only two teams from each conference qualified for the postseason. With the Red Devils now a game up on the Wolverines in the standings, the situation was critical. One more loss, in all likelihood, would have stopped South Carolina’s greatest football dynasty of that era in its tracks.

Willie Varner, already a legend with seven championships to his credit, had a hunch. It had, perhaps, been nagging at his subconscious prior to the Liberty game but now dominated his thoughts in the aftermath.

The decision was clear. A change needed to be made defensively.

Varner had, for years, utilized a 5-4 defensive alignment that placed heavy emphasis on the line of scrimmage with a five-man defensive line bent on pushing back against an opponents’ run game. It was ironic, then, that it was a running back that delivered the Wolverines’ death knell against Liberty, but Tron Jackson’s speed had failed to be contained on the outside by the stronger but slower front being used at the time.

“We had already lost a game earlier in the season to Broome and then we lost to Liberty,” said David Pratt, one of Varner’s most trusted assistant coaches of that time. “You know, I think we just came in and Coach Varner, like a lot of coaches do, just kind of had a feeling or a hunch that what we were doing just wasn’t getting the job done. Maybe he thought we had just become predictable because we had been in the same defense for so many years and maybe we weren’t taking advantage of some of the personnel we had. We had some good athletes on defense that could run and maybe we just weren’t putting them in the best position to win.”

Varner’s 1980 team was, by Woodruff standards, a bit atypical. They were not the biggest or fastest, but were a solid collection of athletes. They also possessed two attributes that are most often naturally attained and not easily coached.

These Wolverines were smart and tough.

“We had experience and the expectation of playing for a state title and that made us better,” said team captain and two-way starter Willie Casey, now a retired U.S. Army Lt. Colonel with 30 years of service. “We played aggressively and expected to shut people out. We played football with a different mindset at that time than you see in today’s game.”

Lineman Scott Weathers recalled, “If I remember correctly, Coach made the change that Saturday morning right after the game. When Coach Varner and his staff decided to make changes, if it was scheme of plays, offensive or defensive formations, we just went with it. We all knew that Coach was going to put us in the best possible positions and lineups to be successful and win ballgames.”

So it was that less than 12 hours following the loss to Liberty, Varner gathered his team for Saturday morning film study and made the announcement. The Wolverines would abandon their patented 5-4 defense and switch to a 50 formation.

In essence, the 50 defense is one designed for total containment. The defensive front would no longer feature five linemen, but rather, defensive personnel would be spread further across the field, containing the edges with the defensive line manning the gaps at the line of scrimmage. It is a defense that requires a high level of discipline to be successful, but Varner figured he had the team to pull it off.

His players needed no convincing. The night before had been their wake-up call and it was heard loud and clear.

“None of us wanted to feel that feeling again so we all bought into the change,” said Johnson. “Any changes the coaches had; we were all in.”

Casey added, “We realized we had good athletes but we were undersized and not fast enough to play a five man front with the players we had. Coach Varner realized we needed more defenders in the up positions within 15 yards of the ball. Our speed, as I said, wasn’t the best but we were aggressive. With the change in defense, we had to play the entire field and control the gaps. The plan was to beat our opponent to the point of attack.”

From inception to activation, Varner installed his new defense in five days. The following Friday his new system would be put to the test against the Wolverines’ county arch-rivals the Chesnee Eagles.

The final score was Woodruff 34 and Chesnee 0. As for the Eagles’ offense against the Wolverines’ revamped defense, Chesnee managed a miniscule 41 total yards and a staggering zero first downs.

Next up was Northwestern, an odd late-season non-conference foe, but one of the top 4A teams in the state. The Trojans managed four first downs and 77 total yards of offense in Woodruff’s 14-0 victory.

Since the defensive shift two weeks prior, Varner had drilled into his team the expectation of 11 hats to the ball on every play, or in football jargon, he wanted his entire defense to converge on the ball carrier. The plan was working.

“Once we started practicing and seeing how the defense was flying to the ball, we knew it was the right move and that it would work,” Weathers said. “No one complained that I remember, and we were just excited to see how it worked in our first game after getting beat.”

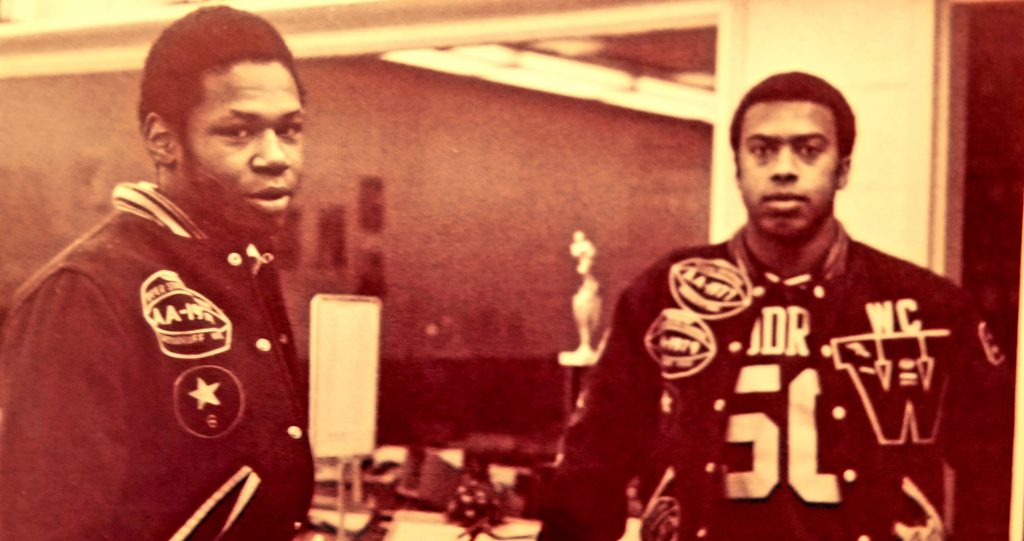

Future Hall of Fame offensive lineman Mitchell Taylor said that, aside from the tactical effectiveness of the new defense, teams were caught off guard by the Wolverines’ new system. In its wake, only three key starters remained two-way players on both offense and defense, Casey, sophomore and future All-American Gene Reeder, and Dale Brown. The added depth and increased stamina on both sides of the ball were immediately noticeable.

“Defensively, it just gave us more people up front,” added Taylor. “It allowed us to keep speed on the field which I think really helped. We were able to do more of a rotation with that defense instead of keeping the same people on the field two ways all the time. It opened things up for a couple of juniors to step in, rotate in, and keep pressuring people on the field but it was just not what people were used to seeing against Woodruff and I think it shocked them a little bit.”

As wildly successful as the early returns were, however, things remained uncertain up until the final game of the regular season.

Liberty had been beaten the week prior and that, coupled with Woodruff’s two victories, had evened the Wolverines and Red Devils atop the region standings with Pendleton, Woodruff’s final regular season opponent. For an outright region crown the Wolverines needed to win and Liberty needed to lose. It was a straightforward scenario.

By that point, though, the engine flames were stoked and the Wolverine machine was rolling. Pendleton stood no chance. For the third consecutive game Woodruff held a team under 100 yards, with the Bulldogs gaining just 64 total and five first downs with a final score of 26-0.

On the same night, Liberty faltered again.

Woodruff was headed to the play-offs as region champions. They would have their chance to play for a sixth consecutive title.

“Once we made the change on defense the whole thing just sort of snowballed,” said Coach Pratt. “We played Chesnee after Liberty but they sure didn’t expect what we came out in on defense. The next team too, they must have thought it was just for that team the week before and they are going to come out in the defense they have been running for so long and so it just caught everyone by surprise. Maybe they weren’t ready for it and they didn’t believe it, but by that time we were two or three scores up on them. It became that way with everyone we played.”

Woodruff would not be tested in the first three rounds of postseason play. The Wolverines easily dispatched Mayewood 61-0 in the first round, followed by a 21-0 drubbing of Abbeville in round two. Lugoff- Elgin was next on the chopping block as Woodruff cast out the Demons 27-0 to win the upper-state championship in the team’s sixth consecutive shutout victory.

“We played with heart, a love for our school, and its tradition, but most of all we played for each other and a desire to never let down, in my opinion, the best high school football coach to walk the sidelines in Willie Varner,” said Weathers.

And the Wolverines were not about to let their coach down in the season’s final, penultimate game. Not after he believed in them to take his plan, placed upon them, learned, and executed in the middle of the season, and brought to fruition with another championship on the line.

They had come too far to fail, but rather, were fated to go out on top with the same vengeance felt by their previous six opponents.

Added Weathers, “We took pride in protecting our endzone and we took pride in beating a team’s will to compete out of them.”

The Swansea Tigers, Woodruff’s title game adversary, were but a postscript in the final chapter of a remarkable story of redemption and perseverance.

Dr. Guy Blakeley, Woodruff’s town and team physician whose son Ashby was a wide receiver on that 1980 squad, is said to have handed a note to a local reporter before that final game and on it was a prediction for the final score.

As the clock hit zero on Dec. 5, 1980 the reporter opened that note to see Doc Blakeley’s prognostication. It was 34-0, the same numbers that were aglow on the scoreboard at Swansea High School’s stadium. Another shutout, a remarkable seventh in a row, and with it an eighth championship for Varner and the Wolverines.

The title was Woodruff’s fifth in six years.

“You just don’t see that kind of defensive dominance anymore,” lamented Pratt. “Making that change, maybe some of our players had lost some confidence in the old defense so this gave them some new hope in doing something different. Coach Varner was like that. He was always good at adapting what he did to his personnel. He was just a very smart coach even though he was very hard-nosed and old school. He wasn’t set in what he was doing just because he had played for five state championships in a row and won four of them.”

Casey roundly agreed.

“Coach Varner was a genius,” he stated. “He knew the kind of players he had and the best position to put us in for us to be successful.”

It was not as if the 1980 Wolverines were ever a team lacking defensively. They were always good, if not quite elite. Woodruff had recorded two shutouts before the change and Liberty’s 19 points was the most scored against the Wolverines all season.

Varner, however, was not going to leave anything to chance. Tron Jackson’s touchdown in the fourth quarter of the season’s seventh game was going to be the last time a Woodruff opponent saw the endzone that year if he had anything to say about it. Varner’s overhaul was one he knew could be trusted to one of the most remarkable teams he ever coached, in a legendary career already etched in immortality.

The 1980 Woodruff Wolverines simply took their place among the pantheon.

“You have to be smart enough to adjust,” said Varner years later. “You can’t force a kid to learn something he can’t do. You see what he does best, and change systems to fit what he can do. The biggest thing, though, is that the guys believed in what I said and didn’t question me. My size helped. I let them pop me around and I popped them around. That helped them respect me. By seeing what I could do, they learned what they could do, and how to go about it.”