Moments That Changed Wolverine History: Part Eight of a 12-Part Series Looking Back at Events Which Changed the Landscape of Woodruff Athletics

By: Garrett Mitchell, Staff Writer

When stories are handed down from one generation to the next, passed from their era by those who witnessed them to the generations and ages that follow, it is presumably easy to blur the line between reality and myth over the passage of time. That is the beauty of legends.

Make no mistake, Woodruff has many of them. Legends, that is. Live in Woodruff long enough and you are going to inevitably talk to somebody who has a story to tell, probably about sports, and, inexorably, you might detect a hint of embellishment. Conversely, you will also find the truth if you listen well enough to the teller and know how to hear between the lines.

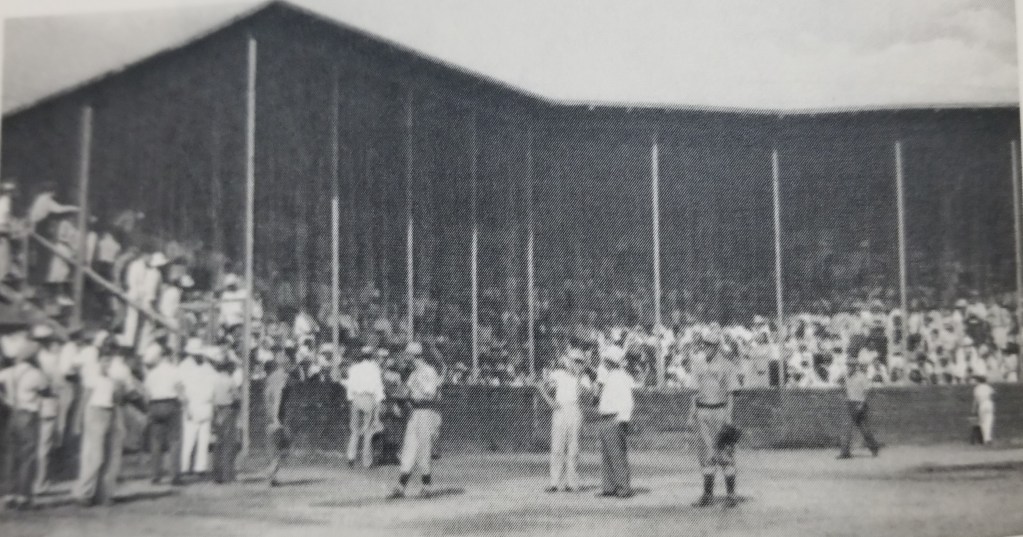

In the Southern United States, from the turn of the 20th century until the 1950s, legends were born between the basepaths of mill hill baseball fields, and in Woodruff, Cross Anchor, and Enoree it was no different. It was competitive baseball, played not only for pride, but for profit and prestige, and at the time served as the plucking grounds for major league baseball teams and a forerunner to what we know now as the minor leagues.

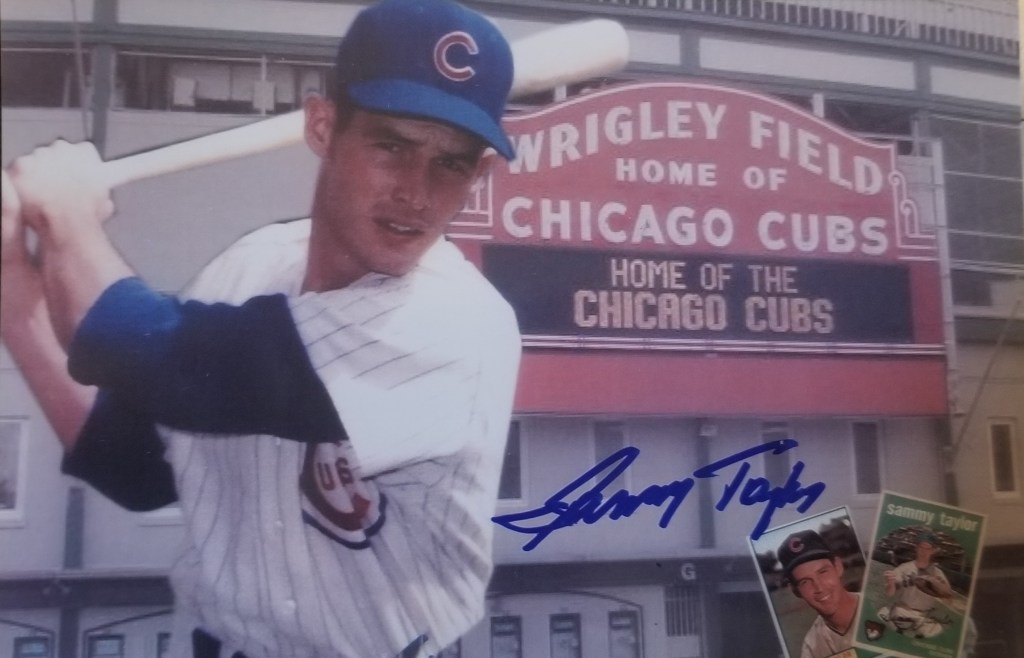

Woodruff was a baseball town in those days. Ask those aforementioned storytellers and you will hear names like ‘Ox’ Taylor, ‘Hamm’ Werner, Sam and Blackie Page, and Sammy Taylor, their fathers, grandfathers, uncles, and brothers. And there are so many more.

These were the legends whose feats are now part of our small-town mythology, but more importantly, they were the solid rocks who formed the foundational bridge from a by-gone era of baseball to the game we know in Woodruff, and across the country, today.

The fruits of the Abney, Mills Mill and Riverdale looms were not just fabric and cloth, but gentlemen who gave their towns an identity through God-given athletic ability, supported by the mills who employed them, and the symbiotic nature of that relationship changed the game, and our little area of Southern Spartanburg County forever.

Perhaps no textile league baseball player in Woodruff became as legendary, though, as Jack ‘Ox’ Taylor.

So many fantastical stories surround Taylor and his exploits that today, those who are still around to recount the tales or those who have had them passed down by friends and family, are perhaps not quite sure where the truth ends and the legend begins.

In her book ‘Mills Mill Pals’, Pamela Chaffin Foster writes of an account given by one Lester Page who resided near Mills Mill Ballpark.

Said Lester, “I had a garden in my backyard, near the ballpark, and I picked more of Ox Taylor’s home run balls out of it than I picked vegetables!”

Or maybe it was the poplar tree behind the right-field fence at Mills Mill that just up and died one day. Locals swear it was doomed by the sheer number of homers that Taylor smashed off its trunk and branches. Or the baseball that Taylor was purported to have hit so far that perhaps it became Earth’s first satellite to reach orbit. After all, nobody ever found the ball, and nobody ever saw it land.

Jack Taylor was larger than life and his talent, and love of the game was passed on to his sons Claudell and Sammy who became legends in their own right.

“Baseball was just great here when I was growing up,” recalled Claudell. “We would go down to Mills Mill and watch my dad play and it was just good times. Great ballplayers back then.”

Claudell still has a lot of memories of watching his father, including admiring the mammoth home run blasts that earned Ox a second moniker as the ‘Babe Ruth of Woodruff’.

“I remember watching him hit a lot of home runs,” continued Taylor. “All of the teams he played against were great. I remember one thing. He hit a line drive to left field and they threw him out at first base because he hit it so hard. And he did hit a lot of home runs into that poplar tree down there and it did die. It sure did. I don’t know if that’s the truth or not but that’s what they say.”

Textile baseball players were an ever-adaptable breed as well. In an era before the prevalence of major league farm systems and widespread minor league clubs, textile baseball was not only a way to supplement the salary of those players who worked in the mills, but it served as a launching point for those players with professional aspirations.

Mills not only competed with one another over industrial productivity but within the ranks of its baseball-playing employees, it also served as a forerunner to what is known today as free agency with employers recruiting players from rival mills to play for them with a promise of salary increases and stipends. The mills became a hunting ground for major league baseball clubs looking for new talent, with one of baseball’s most legendary figures, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson, emerging from the mills of Greenville in the early part of the 20th century.

Woodruff was no different with many of the area’s textile league stars, including those from Enoree to Cross Anchor and even Laurens County going on to play in the big leagues.

In Woodruff, names like Sam Page, Bob Hazle, and Sammy Taylor would rub shoulders with some of the game’s all-time greats either before or after their time in the textile leagues, and they all brought those stories home to their families.

Sam Page, as his daughter Karen Page-Davies recalled, even had a brief encounter with one of the most feared hitters of all-time during his one season playing for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1939.

“Dad would always get stuff in the mail that people wanted him to sign,” she said. “So, one day he got a baseball from a gentleman with a note asking him for an autograph. On the ball was written the number ‘38’. Dad signed the ball and sent it back, and sometime later actually talked to the man and asked him what the number was for. He said ‘Oh, that was the home run you gave up to Ted Williams! It was his 38th home run.’”

She continued, “But dad always made a point to say he struck Ted Williams out three times before he hit that home run and it was going foul but the wind blew it back.”

Sam, who also played baseball and football at Clemson, was a professed junk ball pitcher and left professional baseball after one season in the majors because the coaches in Philadelphia wanted to change his pitching style, something Sam was unwilling to do.

As the Pages and Taylors were carving their legend in Woodruff and beyond, another man was beginning to gain his own notoriety. Nobody knew it at the time, but a young, brash third baseman from Laurens named Clyde ‘Hamm’ Werner would go on to become one of the most recognizable and beloved sports figures the town of Woodruff has ever known.

Werner was a great athlete from a young age said his son, Joey. Drafted by the New York Yankees, Werner played minor league ball from Terre Haute, IN to Jacksonville before enlisting in the Navy as the United States entered the second world war, serving in the Atlantic Theater and putting his baseball career on hold.

While Werner never made it to the big leagues upon returning home, thanks in part to a wartime shrapnel injury to his knee, he maintained friendships with Yankee legends like Yogi Berra and eventually made it to the textile fields of Laurens and Spartanburg Counties.

One intense game at Abney Mill sometime in the late 1940s, and one bench-clearing brawl, however, almost altered the entire course of Woodruff sports history. Textile baseball may have been a family affair, but there was no love lost or punches held on the field, even amongst kin. Werner and his brother June, who played and coached for Abney Mill, would find out the hard way.

Joey recalled the story as his dad had told it….

“Dad was playing for either Watts Mill or Laurens and one day they had a game at Abney Mill in Woodruff, and the place was packed. Uncle June was playing for Abney Mill and was coaching third base and playing catcher. This game was so intense, people were sitting outside watching from trees on a beautiful Saturday afternoon.”

Joey continued, “There was a routine foul pop fly to third and daddy went over to catch the ball and Uncle June wouldn’t move so daddy shoved him. June shoved him back and both benches emptied. They had an all-out brawl right there with two brothers right in the middle of it. They kicked daddy out of the game so he went outside to watch the rest of the game from one of those trees. A policeman came and told him to get out of the tree and to leave town and never come back to Woodruff again.”

Ironically, then, Werner would go on some years later to become the very first youth sports director in the town of Woodruff and his name is still enshrined today on the baseball field at McKinney Park downtown.

Textile League players were as tough as they were resourceful, too, nor was the game policed in the same manner that it is today. It was widely accepted that teams and players would do whatever it took to win. That was up to and including altering baseballs and bats to glean a competitive advantage. After all, it was not simply bragging rights between mills, but also money that was on the line.

Jill Singleton (Page)’s father, Everette, played textile ball from 1938-39 as a catcher and pitcher as well as Singleton’s uncle, Bobby Hazle. Both, she said, left detailed descriptions of how players doctored baseballs to gain the upper hand.

“My dad had this whole folder with stories he had written about how they doctored and fixed the balls, and how they put a cork in the bats to hit better,” she said. “It even surprised me that they put baseballs in the freezer and when they played, you couldn’t hit those balls after they had been in the freezer for so long because they were too hard.”

‘Ox’ Taylor was also Everett Page’s uncle, and Everett passed down stories to his daughter of how he looked up to his legendary uncle and tried to emulate his style of play.

“My dad thought there was nobody greater than ‘Ox’ Taylor,” added Singleton. “He was the Babe Ruth of Woodruff and he wrote stories about how the opposing team would back up every time he came up to bat, but he would usually hit a home run. He was a big man and daddy always talked about how great he was.”

But by the early 1950s textile league baseball and its support were waning. Mill owners were choosing to allocate their financial resources elsewhere to keep up with supply and demand and baseball became less of a priority with professional minor leagues also becoming more popular.

As the great textile leagues and their teams began to shutter, it gave rise to its successors, American Legion baseball and the high school game, both of which were growing in popularity. The aging textile greats now watched their sons and nephews play for their local legion posts or for Woodruff High School, which experienced a rapid boom in talent during the late 1950s.

Claudell Taylor went on to win two state championships as a baseball player at Woodruff High and two more in football, all for a new young coach named Willie Varner. Sammy Taylor went on to play over a decade in the major leagues with the Mets, Cubs, and Indians.

Bobby Hazle played for the Milwaukee Braves, winning the 1957 World Series when the Braves defeated the vaunted Yankees in seven games. His torrid stretch of hitting during the summer of ’57 earned him the nickname ‘Hurricane’ Hazle, after the storm which battered the South Carolina coast three years earlier.

Sam Page’s son, Sammy, would also have a great career in high school and during a short stint in pro ball.

Coach Varner once recounted a visit by a major league scout who came to town and remarked that he could put together an all-star team from Woodruff that would rival any composed of established major leaguers. Varner insisted he was right.

And under Hamm Werner’s leadership, Woodruff became the all-around sports town that people know it as today, with new generations of youth growing to love the game as their fathers and uncles had.

That love of the game is undoubtedly the greatest legacy passed on by those textile league legends to their children, who have since passed it on to every generation that has followed. It can still be seen today whenever Woodruff’s boys of summer take to the diamond. It is a part of Woodruff’s history, and in a transitive way, that of Woodruff High School, too.

“It was for the love of the game,” said Page-Davies. “Not necessarily the amount of money these guys made from it, but it was for love of the game itself. I think that the people who played then didn’t care how much they made, but more about how well they did.”

Claudell Taylor added, “We all learned a lot from my dad and the men he played with. To be a good sport, keep your eye on the ball, and watch it until it hits the bat and you won’t have any problems.”

Great words of advice that stand the test of time, even if they still have not found ‘Ox’ Taylor’s baseball.

Chicago Cub, Sammy Taylor [Photo Courtesy of Pamela Chaffin Foster]

Mills Mill Park before a game in the 1930s [Photo Courtesy of Pamela Chaffin Foster]